Thank you, Gregory Peck!

Quite honestly, I cannot remember a time growing up when I thought of becoming a priest, let alone a missionary priest. In the suburban environment of East Aurora, N.Y., where I was raised, priesthood was not one of the choices presented at our yearly school career day. The priesthood was seen as something “no one did anymore.” I dreamed of being a lawyer. But today I am a missionary priest in Tanzania because of a spark lit by an old black-and-white film.

I was midway through my senior year at Canisius College in nearby Buffalo and had already been accepted at two top law schools. One night, tired of studying, I drove to the local art film theater, where it was Gregory Peck Week. That evening they were showing Keys to the Kingdom, in which Peck plays a missionary priest. The movie flashes back to the priest’s life in prerevolutionary China. What moved me so much was the unvarnished portrayal of mission life, including the courage it often demands in the face of cultural misunderstanding as well as the satisfaction it brings in seeing a community one has struggled to build grow and prosper.

This is not to say that when I stepped out of the theater, I decided to become a priest. But it was a conversion of sorts—no falling off a horse, no blinding light, no voice from above. I only knew that I wanted more than I had planned for myself.

I was midway through my senior year at Canisius College in nearby Buffalo and had already been accepted at two top law schools. One night, tired of studying, I drove to the local art film theater, where it was Gregory Peck Week. That evening they were showing Keys to the Kingdom, in which Peck plays a missionary priest. The movie flashes back to the priest’s life in prerevolutionary China. What moved me so much was the unvarnished portrayal of mission life, including the courage it often demands in the face of cultural misunderstanding as well as the satisfaction it brings in seeing a community one has struggled to build grow and prosper.

This is not to say that when I stepped out of the theater, I decided to become a priest. But it was a conversion of sorts—no falling off a horse, no blinding light, no voice from above. I only knew that I wanted more than I had planned for myself.

Temporary measures

The very next week I stopped to read one of the hundreds of fliers plastered on the campus billboards. It was an invitation to find out more about the Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC). My college was a Jesuit school, and each year some of the graduates participated in volunteer commitments the Jesuits sponsored throughout the United States. I decided to apply.

When the acceptance letter arrived and I was informed I had been assigned to Alaska, I told my family, friends, and myself this would be a temporary detour on my life’s course. I received a deferment from law school and left for Alaska shortly after graduation from college.

The two years I spent on the treeless tundra between the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers in Bethel, Alaska, opened my heart to mission as a possible way of life. Living with the Yupik Eskimo and Athabascan Native Americans further expanded my horizons and helped me see life in a more creative way.

When I returned home, I found out how true the JVC motto is. I was indeed “ruined for life.” I didn’t want to pick up the strands that had characterized my life in the past. As one Maryknoller aptly puts it, “You can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube once it’s out.” My family and friends, while very loving, could not understand that the “temporary break” had become a life choice. The universal opinion seemed to be that if I had to be a priest, why not be one in the United States?

Somehow I knew my vocation made sense only in the context of overseas mission, and I set out to look at different religious communities. I settled on Maryknoll because its primary focus was overseas mission. I was attracted by the image Maryknoll presented of a “family in mission, ”priests, brothers, sisters, lay singles and families working together around the world. The many Maryknoll martyrs and their commitment to the poor also made a deep impression on me.

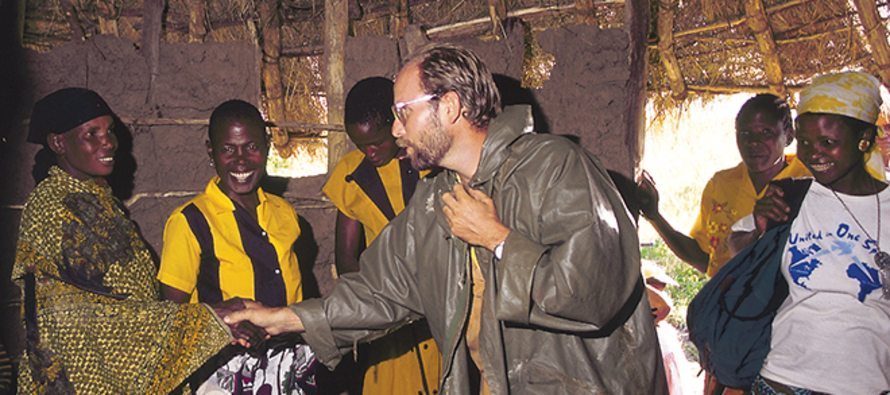

After seven years in seminary training (three of which I spent in Caracas, Venezuela) and nine years as a priest in Tanzania, I can say I made the right choice. There have been difficult situations along the way, but God always seems to surround me with caring and supportive individuals who help me get past the difficult times.

When the acceptance letter arrived and I was informed I had been assigned to Alaska, I told my family, friends, and myself this would be a temporary detour on my life’s course. I received a deferment from law school and left for Alaska shortly after graduation from college.

The two years I spent on the treeless tundra between the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers in Bethel, Alaska, opened my heart to mission as a possible way of life. Living with the Yupik Eskimo and Athabascan Native Americans further expanded my horizons and helped me see life in a more creative way.

When I returned home, I found out how true the JVC motto is. I was indeed “ruined for life.” I didn’t want to pick up the strands that had characterized my life in the past. As one Maryknoller aptly puts it, “You can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube once it’s out.” My family and friends, while very loving, could not understand that the “temporary break” had become a life choice. The universal opinion seemed to be that if I had to be a priest, why not be one in the United States?

Somehow I knew my vocation made sense only in the context of overseas mission, and I set out to look at different religious communities. I settled on Maryknoll because its primary focus was overseas mission. I was attracted by the image Maryknoll presented of a “family in mission, ”priests, brothers, sisters, lay singles and families working together around the world. The many Maryknoll martyrs and their commitment to the poor also made a deep impression on me.

After seven years in seminary training (three of which I spent in Caracas, Venezuela) and nine years as a priest in Tanzania, I can say I made the right choice. There have been difficult situations along the way, but God always seems to surround me with caring and supportive individuals who help me get past the difficult times.

Soup’s on!

My ministry here in Tanzania has involved me in basic evangelization and service to the needs of the rural poor, mainly farmers. Like most Maryknoll missioners, I aim to work myself out of a job. To sum up what I do, I refer to a story I heard as a child called “Stone Soup.” It’s about a young man who walks into a town in a country in the middle of civil war. The people have suffered great hardships from armies passing through. The man sits in the town center and waits. Slowly, the townspeople come out from their hiding places to find out who this stranger is.

The man takes a smooth grey stone out of his bag. He claims he can make the best soup they ever tasted from that stone. Suspicious but curious, they supply him with a large pot, water and firewood. He places the stone in the pot.

After a while, he tastes the soup and finds it wonderful but says, “If only I had some onions, the soup would be beyond belief.” So one of the people brings out a hidden cache of onions. In this manner, the man gets the people to add carrots, potatoes, beef, salt, cabbage: in short, all the ingredients they had hidden from the soldiers. Soon all the people are enjoying a feast.

As a missioner I try to build up the local community by uncovering the many gifts with which God has blessed the people. It involves encouraging their self-confidence and helping them see themselves as loved and cherished by God. I am like the young man in the story who, after the people have begun to trust themselves, takes the stone and moves on to a new town.

I look forward to continuing this journey for a long time. Many thanks to you, Gregory Peck, wherever you are.

The man takes a smooth grey stone out of his bag. He claims he can make the best soup they ever tasted from that stone. Suspicious but curious, they supply him with a large pot, water and firewood. He places the stone in the pot.

After a while, he tastes the soup and finds it wonderful but says, “If only I had some onions, the soup would be beyond belief.” So one of the people brings out a hidden cache of onions. In this manner, the man gets the people to add carrots, potatoes, beef, salt, cabbage: in short, all the ingredients they had hidden from the soldiers. Soon all the people are enjoying a feast.

As a missioner I try to build up the local community by uncovering the many gifts with which God has blessed the people. It involves encouraging their self-confidence and helping them see themselves as loved and cherished by God. I am like the young man in the story who, after the people have begun to trust themselves, takes the stone and moves on to a new town.

I look forward to continuing this journey for a long time. Many thanks to you, Gregory Peck, wherever you are.

Adapted and used with permission from an essay in Why Not Be a Missioner? published in 2002 by Orbis Books.

Tags

Related

- African dream: my 17 years in Kenya

- Lessons in love from central Brazil

- Missionary sister falls in love

- Sister Dorothy Stang: Her dying shows us how to live

- Refugee crisis 'a battle for our humanity' in Jordan

- Fighting gangs one youth at a time

- Starting over from scratch

- My mission: To be an instrument in God’s hands

- Beginning again in Ireland

- And Jesus said, “Feed my lambs.” Read More

Most Viewed

- Find your spirituality type quiz

- FAQs: Frequently asked questions about vocations

- Celibacy quiz: Can you live a celibate life?

- Resources for older discerners or those with physical and developmental differences

- About Vocation Network and VISION Guide