Family matters

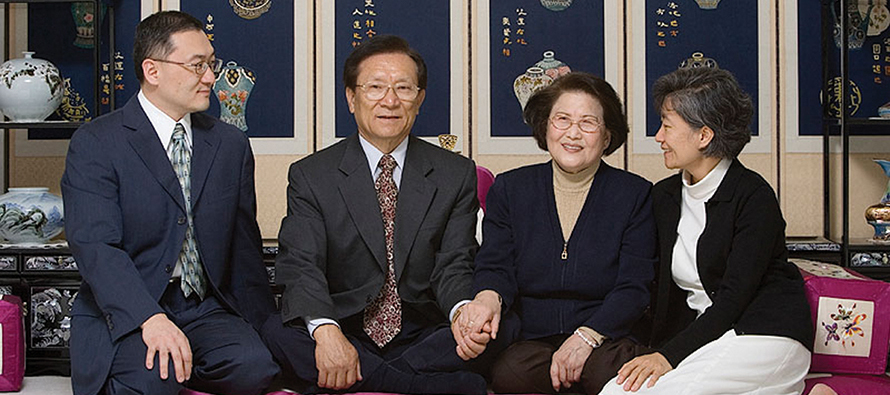

Image: Sister Helena Im, O.P. (on the far right) with her brother, Chris (far left); her father, Peter; and her mother, Anna.

WHEN HELENA IM told her parents she wanted to be a nun, they were aghast. They had been arranging for her to meet a young man they had hoped would marry her. As Korean immigrants, they fully expected to have a say in her future.

“Both of my parents were very upset,” recalls Im, now a Dominican sister in Fremont, California. “My father wanted to disown me. But by the time I entered the community, I knew I had the full support of both of my parents.”

Im’s story of parental revulsion-turned-to-approval is hardly unusual. Catholics of every ethnic background have long had to deal with varying levels of family support, questioning, or resistance to their vocations. Although resistance can be disappointing, vocation ministers who usher in new members agree that opposition usually gives way to approval, although it may take a while.

Natural questions

Vocation ministers say that most families have questions about a member who is joining a religious community or becoming a diocesan priest. Will loved ones be happy in the life? Can they be happy? Will family members be cut off from seeing them? What about completing a college education before committing to a community or diocese? What about grandkids? What about continuing the family name? If loved ones are leaving behind careers and homes, will they be left with nothing if a church vocation doesn’t work out?

“Sometimes women are upset that their parents seem opposed to them entering religious life, but I usually tell the women that the questions are coming out of a place of love,” says Sister Anita Louise Lowe, O.S.B., vocation minister for the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand, Indiana. Mothers and fathers are doing what they’ve always done, says Lowe: watching out for the best interest of their child.

Of course, what exactly is the “best interest” of an adult child is open to interpretation. Today’s Catholic parents are more likely than past generations to be cynical about or detached from the Catholic Church. Thus, they may question a religious vocation more. Older religious recall a time when American Catholics generally were proud and supportive when a child went off to the seminary or convent. For Catholics in previous generations, a child in the priesthood or religious life was a badge of honor, a sign that they were a good family and their child was fulfilling the American dream of ascending the social ladder. The big Catholic families of the past also ensured that some children would marry and have grandchildren, even if others became brothers, sisters, or priests.

Complicating things further is an economic shift. Although a church vocation never has held a promise of riches, American Catholics are wealthier than ever now, which makes priesthood or religious life a downward economic move for many. In addition, the tainted image of the church following sex scandals, money mismanagement, and other misdeeds has made religious life and priesthood less prestigious than in the past. All these factors affect how parents and other family members react to church vocations.

How much support?

There is no magic formula that will tell how understanding or supportive a family might be. In general, Catholics who have had positive relationships with priests, brothers, or sisters are more supportive than families that are unfamiliar with Catholicism or religious life.

Vocation ministers give wildly varying answers when asked what proportion of families are positive about a child entering religious life or priesthood. Some say only about 20 percent greet the news happily. Others say the vast majority are in favor of their children joining religious life or priesthood; they just have questions to iron out. Most do agree that a small fraction, maybe 10 or 20 percent, is vigorously opposed, sometimes to the point of actively trying to sabotage their adult child’s vocation. An even smaller percentage is vigorously enthusiastic, maybe around 10 percent. Finally, a very few, maybe 5 percent or less, will push an adult child into religious life or priesthood.

Happy or sad about a church vocation for their child, one question parents frequently bring up is: What will happen to us if we need help in our old age? If their child is busy being a pastor or ministering in some other region, parents worry about how the daughter or son can help with family matters. With most Catholic families having only a few children, this question often arises, says Sister Lowe. “We reassure them that sisters from our community have requested periods of time away in order to help with family members who had a health issue or some other crisis. There’s no guarantee of how that might look for their daughter’s situation some day, but we are open to it,” she says. Other religious orders, too, say they deal with the needs of birth families on a case-by-case basis.

Economic issues

When Brother Jesús Alonso, C.S.C., a member of the Brothers of Holy Cross in San Antonio, Texas, was considering religious life, he was less focused on time off for health crises than he was concerned about his family members living in poverty. Having grown up in a large migrant worker family, Alonso was only the second of his six brothers and sisters to graduate from college. His focus throughout his studies had been to get a degree in computer science, find a good job, and help provide for his family economically.

When Alonso felt called to be a brother, the economic concern for his parents and siblings was a major impediment. “The vow of poverty was not a big issue for me personally. I knew there was more to life than that. But I still had to go back to my parents and explain this vocation. That was a significant moment in our relationship,” says Alonso. His dad agreed with him that Alonso ought to be supporting the family. His mother, however, told him, “I never expected you to support us. What matters is that you choose correctly what is right.”

Now, four years later, says Alonso, both his parents “are more at peace with the decision to be a brother.” His parents have met members of his religious community, although he says, “I wish my parents knew the language to get to know the brothers better.”

Culture clash?

Language, faith, and culture certainly influence the way parents take the news about their offspring’s desire for vows or ordination, as well as how prospective priests, sisters, and brothers cope with family relationships. Sister Im and her parents saw vocation decisions through the lens of their Korean culture, which emphasizes family and community ties. “American society says, ‘Pursue your individual dream,’ but for other cultures, who you are is very connected to relationships with others,” says Im.

Asian Americans and many Latinos can be torn between their deep desire—which is pulling them into religious life or priesthood—and their families, who may discourage such plans. For Asians, a good person pleases his or her parents. So how can you be a good person and become a priest, brother, or sister if that displeases your parents? “The situation can set off a considerable internal struggle,” says Im, who is now a vocation minister herself. Her solution when she encounters family conflicts such as she herself experienced is to wait, pray, and visit. That is how her parents eventually came to embrace her decision to be a nun.

Time spent together allows families, religious life candidates, and their communities to get to know each other. Most religious communities invite parents and siblings of serious candidates to come visit. Many vocation ministers routinely make visits to the family home for those closely considering the life.

Deborah Mitchell, who is entering the Bon Secours Sisters, slowly introduced her non-Catholic father to the idea of her being a sister (her mother is deceased). “My dad met Sister Pat [the vocation minister] and I showed him the Bon Secours website,” says Mitchell. “He told me, ‘Deb, I know you, and I know that you research things and check them out first. Since you feel called to this, I support you.’ That meant so much to me.” Mitchell’s birth-sister is less enthusiastic but not opposed.

Have a great life!

Regardless of how a person’s family first reacts to the news of a church vocation, most people entering religious life cannot ask for more than what Deborah Mitchell received from her father on the day she entered her community in a formal church ritual.

“On the day of the ceremony my dad was hugging the sisters, and he hugged me, and he said, ‘Have a great life!’ He had a little bit of tears in his eyes when he said that. I think he realized this was a lifetime commitment for me, but at the same time it was a life-giving commitment for me.”

WHEN HELENA IM told her parents she wanted to be a nun, they were aghast. They had been arranging for her to meet a young man they had hoped would marry her. As Korean immigrants, they fully expected to have a say in her future.

“Both of my parents were very upset,” recalls Im, now a Dominican sister in Fremont, California. “My father wanted to disown me. But by the time I entered the community, I knew I had the full support of both of my parents.”

Im’s story of parental revulsion-turned-to-approval is hardly unusual. Catholics of every ethnic background have long had to deal with varying levels of family support, questioning, or resistance to their vocations. Although resistance can be disappointing, vocation ministers who usher in new members agree that opposition usually gives way to approval, although it may take a while.

Natural questions

Vocation ministers say that most families have questions about a member who is joining a religious community or becoming a diocesan priest. Will loved ones be happy in the life? Can they be happy? Will family members be cut off from seeing them? What about completing a college education before committing to a community or diocese? What about grandkids? What about continuing the family name? If loved ones are leaving behind careers and homes, will they be left with nothing if a church vocation doesn’t work out?

“Sometimes women are upset that their parents seem opposed to them entering religious life, but I usually tell the women that the questions are coming out of a place of love,” says Sister Anita Louise Lowe, O.S.B., vocation minister for the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand, Indiana. Mothers and fathers are doing what they’ve always done, says Lowe: watching out for the best interest of their child.

Of course, what exactly is the “best interest” of an adult child is open to interpretation. Today’s Catholic parents are more likely than past generations to be cynical about or detached from the Catholic Church. Thus, they may question a religious vocation more. Older religious recall a time when American Catholics generally were proud and supportive when a child went off to the seminary or convent. For Catholics in previous generations, a child in the priesthood or religious life was a badge of honor, a sign that they were a good family and their child was fulfilling the American dream of ascending the social ladder. The big Catholic families of the past also ensured that some children would marry and have grandchildren, even if others became brothers, sisters, or priests.

Complicating things further is an economic shift. Although a church vocation never has held a promise of riches, American Catholics are wealthier than ever now, which makes priesthood or religious life a downward economic move for many. In addition, the tainted image of the church following sex scandals, money mismanagement, and other misdeeds has made religious life and priesthood less prestigious than in the past. All these factors affect how parents and other family members react to church vocations.

How much support?

There is no magic formula that will tell how understanding or supportive a family might be. In general, Catholics who have had positive relationships with priests, brothers, or sisters are more supportive than families that are unfamiliar with Catholicism or religious life.

|

|

Brother Jesus Alonso, C.S.C. (in white sweater) with his family.

|

Happy or sad about a church vocation for their child, one question parents frequently bring up is: What will happen to us if we need help in our old age? If their child is busy being a pastor or ministering in some other region, parents worry about how the daughter or son can help with family matters. With most Catholic families having only a few children, this question often arises, says Sister Lowe. “We reassure them that sisters from our community have requested periods of time away in order to help with family members who had a health issue or some other crisis. There’s no guarantee of how that might look for their daughter’s situation some day, but we are open to it,” she says. Other religious orders, too, say they deal with the needs of birth families on a case-by-case basis.

Economic issues

When Brother Jesús Alonso, C.S.C., a member of the Brothers of Holy Cross in San Antonio, Texas, was considering religious life, he was less focused on time off for health crises than he was concerned about his family members living in poverty. Having grown up in a large migrant worker family, Alonso was only the second of his six brothers and sisters to graduate from college. His focus throughout his studies had been to get a degree in computer science, find a good job, and help provide for his family economically.

When Alonso felt called to be a brother, the economic concern for his parents and siblings was a major impediment. “The vow of poverty was not a big issue for me personally. I knew there was more to life than that. But I still had to go back to my parents and explain this vocation. That was a significant moment in our relationship,” says Alonso. His dad agreed with him that Alonso ought to be supporting the family. His mother, however, told him, “I never expected you to support us. What matters is that you choose correctly what is right.”

Now, four years later, says Alonso, both his parents “are more at peace with the decision to be a brother.” His parents have met members of his religious community, although he says, “I wish my parents knew the language to get to know the brothers better.”

Culture clash?

Language, faith, and culture certainly influence the way parents take the news about their offspring’s desire for vows or ordination, as well as how prospective priests, sisters, and brothers cope with family relationships. Sister Im and her parents saw vocation decisions through the lens of their Korean culture, which emphasizes family and community ties. “American society says, ‘Pursue your individual dream,’ but for other cultures, who you are is very connected to relationships with others,” says Im.

Asian Americans and many Latinos can be torn between their deep desire—which is pulling them into religious life or priesthood—and their families, who may discourage such plans. For Asians, a good person pleases his or her parents. So how can you be a good person and become a priest, brother, or sister if that displeases your parents? “The situation can set off a considerable internal struggle,” says Im, who is now a vocation minister herself. Her solution when she encounters family conflicts such as she herself experienced is to wait, pray, and visit. That is how her parents eventually came to embrace her decision to be a nun.

Time spent together allows families, religious life candidates, and their communities to get to know each other. Most religious communities invite parents and siblings of serious candidates to come visit. Many vocation ministers routinely make visits to the family home for those closely considering the life.

Deborah Mitchell, who is entering the Bon Secours Sisters, slowly introduced her non-Catholic father to the idea of her being a sister (her mother is deceased). “My dad met Sister Pat [the vocation minister] and I showed him the Bon Secours website,” says Mitchell. “He told me, ‘Deb, I know you, and I know that you research things and check them out first. Since you feel called to this, I support you.’ That meant so much to me.” Mitchell’s birth-sister is less enthusiastic but not opposed.

Have a great life!

Regardless of how a person’s family first reacts to the news of a church vocation, most people entering religious life cannot ask for more than what Deborah Mitchell received from her father on the day she entered her community in a formal church ritual.

“On the day of the ceremony my dad was hugging the sisters, and he hugged me, and he said, ‘Have a great life!’ He had a little bit of tears in his eyes when he said that. I think he realized this was a lifetime commitment for me, but at the same time it was a life-giving commitment for me.”

Tags

Related

- Religious making a difference

- Religious seekers in legal limbo

- Mercy meets at the border

- Religious life: The call continues

- Vocation Basics: Essentials for the vocation journey

- Community life: A place to call home

- A charism encourages a caring ministry

- The four main types of religious life

- Our newest religious possess an age-old Christian virtue: hope

- Celibacy steeped in a whole lot of love Read More

Most Viewed

- Find your spirituality type quiz

- FAQs: Frequently asked questions about vocations

- Celibacy quiz: Can you live a celibate life?

- Resources for older discerners or those with physical and developmental differences

- About Vocation Network and VISION Guide

Carol Schuck Scheiber is VISION's content editor.

Carol Schuck Scheiber is VISION's content editor.