|

The short answer to this question: “A lot.” There are 73 books included in the Bible used by Catholics. By one estimate, the word “God” appears 3,358 times in those books and the word “Lord” another 7,736 times. So where to begin?

God wants to be known by humanity and is constantly reaching out to us to make that possible. From God’s stroll in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:8) right through to God’s definitive revelation in the person of Jesus and the coming of the Holy Spirit, God is involved in a constant process of communication with humanity.

How can we get a better idea of what God is like? The Letter to the Romans gives us one place to start: Take a good look at God’s creation: “Ever since the creation of the world, God’s invisible attributes of eternal power and divinity have been able to be understood and perceived in what God has made” (Romans 1:20). The wonders of the natural world give us hints of God’s qualities. Be sure to stay in touch with the beauty of God’s creation by making some time for a walk in the woods, a weekend of camping, an evening of gazing at the night sky.

Above all, we learn about God through Jesus because he lived with and as one of us. When we look at the testimony of scripture, we see that Jesus represents the fullness of God’s revelation to humanity. As the Letter to the Hebrews puts it: “In times past, God spoke in partial and various ways to our ancestors through the prophets; in these last days, he spoke to us through a son . . . who is the refulgence [radiance] of his glory, the very imprint of his being” (Hebrews 1:1-3). Or, as Jesus himself explained to the apostle Phillip: “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9).

By his example Jesus shows us that God possesses and expresses the noblest of qualities to perfection—truth, beauty, justice, mercy, grace, goodness, compassion—in a word, love. In fact, Jesus lived and suffered as one of us because, in the well-known quote from John 3:16, “God so loved the world.” What greater love is there than “to lay down one’s life for one’s friends,” as Jesus did (John 15:13)?

We also know God through the gift of the Holy Spirit, who appears throughout Hebrew scripture—beginning with the second verse of Genesis where the Spirit, in the form of a “mighty wind,” hovered over the waters. Midway through Hebrew scripture we find the psalmist’s plea, “Do not drive me from before your face, nor take me from your holy spirit” (Psalm 51:13).

The Holy Spirit appears in many passages in the New Testament. Jesus promised to send his followers a Helper or Comforter who would be with them always (John 14:16), and in the “great commission” at the end of the Gospel of Matthew, one of the lynchpins of Christian faith in the Trinity, Jesus says, “Go, therefore,and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19).

The Holy Spirit comes to the forefront in the Acts of the Apostles, most famously at Pentecost, when members of the early church “were all filled with the holy Spirit and began to speak in different tongues,as the Spirit enabled them to proclaim” (Acts 2:4).

While the Bible does indeed provide us with a great variety of testimony to the manifold, mysterious, and wonderful nature of God, in our human experience getting to know God doesn’t happen all at once. It is a lifelong process that unfolds in spiritual reading and reflection, prayer, and in our interactions with others—in “fellowship,” to use the church term.

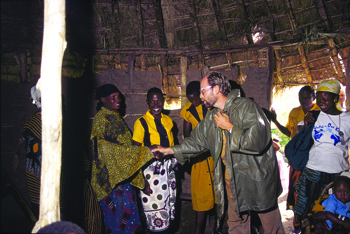

Fellowship happens when we gather to worship, surely, but also in our homes and offices and in all our daily interactions with others, both casual and intimate. When we interact with a sense of God’s presence, even when there are only “two or three” of us, we know that Jesus is there with us (Matthew 18:20).

Perhaps one of the most useful of the many titles found in the Bible for God is Immanuel or Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14), which literally means “God-with-us.” That conviction, firmly rooted in our hearts, may be all we ever need to know about our loving God.

Resources

• See pt. 1, sec. 1, ch. 2 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “God Comes to Meet Man,” for a description of God’s interaction with humanity

• For children ages 4-9: Images of God for Young Children by Marie-Helene Delval, illustrated by Barbara Nascimbeni, Eerdmans, 2010