The celebration of Lent is a long-established tradition in the church—and I use the word celebration deliberately. The prayers of the liturgy refer to Lent as “this joyful season.” Though the character of the season is penitential, the intent of Lent is to prepare our dispositions for the greatest feast of the church year, the always-jubilant Easter. With all that to look forward to, Lent could hardly be a mournful time.

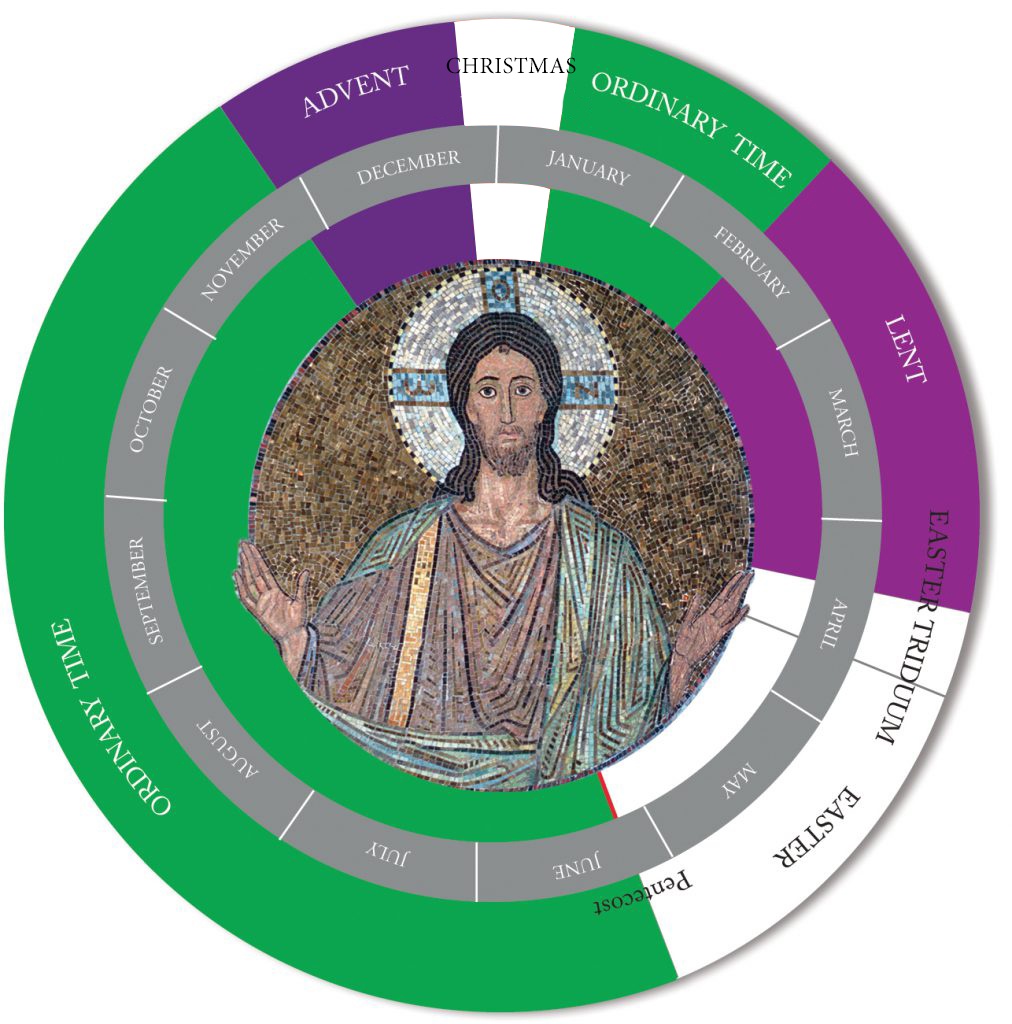

So where did Lent come from? Let’s start by saying that Christianity embraces one key belief: the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. This central article of faith shapes everything we do as Christians, how we live and die, and certainly how we express our faith in worship. Easter is therefore the primary day of rejoicing. Every Sunday is considered a “little Easter,” a commemoration of how Jesus triumphed over sin and death through the power of God for the sake of humanity’s emancipation from those ancient twin evils that bound it. The entire church year spins on the axis of Easter faith.

In the first three centuries of the church Christians prepared for this mother-of-all-feasts by fasting—between two days to a week depending on local custom. In Rome the “paschal fast” may have lasted as long as three weeks. This extended fast was linked to the preparation of new members for baptism at the Easter Vigil.

By the 4th century a full 40-day period of preparation was observed, imitating the 40-day fast of Jesus in the desert before undertaking his great mission. Fasting and prayer were natural components of the season because that’s how Jesus prepared himself. Almsgiving was added to the practices of Lent as it, too, was a traditional way of making sacrifice to God in the wake of sinfulness. Following a calendar of feasts and seasons dependent on one’s faith is an idea rooted in Judaism. The Law of Moses established fixed times annually to recall the saving actions of God, centered on the commemoration of Passover. A liturgical calendar allowed Israel to practice gratitude and thanks, repentance and conversion, each in accord with the natural seasons, rains, and harvests. A cycle of liturgy also provided a way to instruct new generations about the faith in ritual and storytelling.

Easter, the Christian Passover, was fixed by the Council of Nicaea in 325 to coincide with the first full moon after the vernal equinox. That makes Lent the annual “springtime” of faith, quite literally, as the word Lent means "spring."

Scripture

• Mark 1:12-13; Matthew 4:1-2; Luke 4:1-3; Leviticus 23

Online

• “Grave matters: Take away the Resurrection and the center of Christianity collapses,” article by N. T. Wright

• For fun: Wiki article on “computus,” the complicated story of calculating the date of Easter

Books

• Embracing the Sacred Seasons of Lent and Easter: Daily Reflections and Prayers by Janis Yaekel (Twenty-Third Publications, 2005)

• Living Liturgy: Spirituality, Celebration, and Catechesis for Sundays and Solemnities (Liturgical Press)

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.