Persistent call pays off

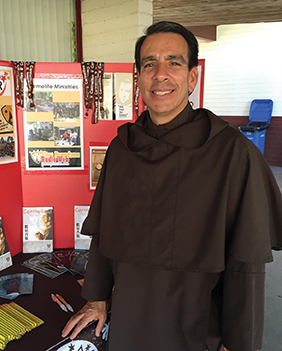

Image: Father Paul Henson, O.Carm. (center right) with some of the men who entered his community in recent years.

For those who think the road to religious vocation is a straight path, meet Father Paul Henson, O.Carm. Henson’s route to the priesthood wandered in and out of seminary, into a career as a teacher, through a season in his 20s of considering marriage and family—but he kept hearing a call to religious life.

Finally, at age 30, he answered—and his ministry since as a Carmelite priest has taken him to Mexico and Peru and into education administration as principal of Crespi Carmelite High School in Encino, California. He’s now a vocation director for the Carmelites, serving the Province of the Most Pure Heart of Mary in Darien, Illinois, living in a priory next to a Carmelite high school in Tucson, and traveling to Chicago to serve month-long stretches at the pre-novitiate house three or four times a year.

His advice to young people considering religious vocation: Pray for God’s guidance and take the time to “experiment with life, to look, to investigate,” to consider other paths and opportunities. Also, “trust what’s going on in your heart. God’s inviting you to this.”

How can I make a splash?

Henson has known his whole life what it’s like to grapple with figuring out your place in the world.

He grew up in the suburbs of Los Angeles. While his neighborhood was ethnically mixed and his own family second-generation Mexican-American, his parish was run primarily by Irish priests. His family was not traditional in the American sense—when he was young, his mother died and his father left, and he grew up in his mother’s intergenerational, bilingual family, led by his maternal great aunt, Luz Salcedo, who was very religious and who gathered Henson and his cousins regularly at dawn to pray the rosary, sometimes in English, sometimes in Spanish.

Born in 1964, “I grew up at a time when you were assimilated,” Henson says. “You were supposed to be white. You had to speak English. You didn’t really want to speak Spanish with your classmates,” or to look different. There wasn’t, for him, a role model of a Mexican-American priest. Yet he felt called to be one.

When Henson was five, American astronauts landed on the moon. “I remember sitting in front of our little black-and-white TV,” watching those historic first steps and thinking “that I wanted to make a difference in the world,” Henson recalls. “I wanted to make a splash. I wanted people to remember me.”

As he grew older, that sense of wanting to be special shifted to a more selfless thinking that “I wanted to do something that would impact people’s lives.”

He had become an altar server, and when he watched carefully as the priests celebrated Mass, he felt, “I want to do that.”

Maybe I should be a priest

He attended a Catholic elementary school, where, when he was in the sixth grade, a group of seminarians came to speak to his class. He remembers they were nicely dressed—black pants, white shirts, blazers—and they talked about both the academics and the sports the high school seminary offered. “They made it sound so fun,” Henson says. He went home and told his great aunt, “I want to be a priest.”

So for high school, he enrolled in St. Vincent’s Seminary in Montebello, California. He was all lined up, it appeared, to enter the priesthood. Except that he wasn’t. Henson stayed in the seminary only two years—leaving after that to attend a Catholic boys’ high school after deciding the seminary “just wasn’t for me,” in part because he wanted to date girls (which he couldn’t even then, officially, because his great aunt was so strict).

After graduating from high school, Henson attended St. John’s Seminary College in Camarillo, California, graduating in 1986 with a degree in philosophy. He still felt pulled toward priesthood but not certain—he’d met a woman and fallen in love. He moved to North Hollywood and took a job with Catholic Charities working with runaway teenagers.

One Saturday he went to the local Carmelite parish for confession. But when he got there, he found the confessional empty. He walked outside and saw a guy wearing shorts, a tank top, and flip-flops sitting on the steps, and he asked him, “Do you know where the priests are?”

The man answered, “I’m a priest.” They went to the confessional, and after absolution, they continued their conversation outside. “I told him my story,” Henson says. “He said, ‘Maybe you should think about becoming a Carmelite.’ I remember thinking, ‘Wow, they’re not pretentious, they’re regular guys. They care about you as a person.’ ”

Carmelite on the second try

The priest introduced Henson to other Carmelites. He visited with them for about a year and in 1989 applied to join the order. “I got accepted, but I got cold feet, kind of at the last minute.” And he backed out. Henson began working as a teacher, first at a Catholic elementary school and later a high school. “There was always a sense of service,” he says, and always in connection with the church.

Because Henson had grown up with the loss of his parents, “I was just so grateful that God took care of me,” giving him a loving family nonetheless, Henson says. He eventually decided, “I’m going to live my life in gratitude for God’s care of me.”

In 1995—nine years after nearly joining the Carmelites the first time, this time at age 30—Henson applied to join the Carmelites again and was ordained in 2002. “Eventually I just said, this is where God wants me,” Henson says. “I just have to do it.”

In time Henson’s community assigned him to work at Crespi Carmelite High School, where he served as principal. Father Thomas Schrader, a Carmelite and president of Bishop Ward High School in Kansas City, worked with Henson at Crespi—Schrader was president there then. “He’s a really high energy person,” Schrader says of Henson, and also prayerful and committed to social justice. “He liked to put the students first, that was really his thing.”

Henson says he loved the “excitement and energy” of the classroom and the sense of creativity it sparked “to really become a mentor, to walk with the kids in their sorrows and their joys.”

Feeding a hunger for church

Before he arrived at Crespi, he worked in Mexico with Schrader at rural missions attached to a Carmelite parish in Torreón in the state of Coahuila, in the northern desert. “People were living in little shacks they kind of put together,” Schrader says. “It eventually became a neighborhood. People would put together what they could and build as they had funds. The real eye-opener here was the migration of the people to the church as a place that was a familiar home to them,” despite not really having homes of their own.

Henson said he worked with people who were “so hungry to learn about church, to learn about how God acts in our lives in very concrete ways.” Because there was no church building, on Sundays before Mass the children would sprinkle water on the dirt to keep down the dust. Week after week, “they would make church,” Henson says. He remembers also what a wise older man living in the Andes Mountains in Peru told him. “Be careful, Paul, what you do in these mountains. Recognize that God’s footprint is already there. God’s already there in the people. You don’t come in telling them what to do. You respect where they’re at.”

Later, he applied what he’d learned there to his work at Crespi. Every month, he’d offer “Coffee with Father Paul”—an hour-long chance for parents to discuss their concerns. He started each session with lectio divina, a form of scripture mediation, and prayer and then talk about issues. Parents would tell him they’d arrived with so many worries and concerns, but after praying together, “it’s like the problem I came with all of a sudden wasn’t that big of a problem,” they would say to him.

Inspiring vocations at a quiet pace

In 2013 Henson took on a new role, as a vocation director for the Carmelites, traveling around the country and working with inquirers, visiting parishes, leading retreats, and visiting youth conferences and schools.

“He brings the same energy, the same enthusiasm, the same genuine interest in young people and their journeys,” says Brother Daryl Moresco, the Carmelites’ provincial director of vocations and pre-novitiate director. “He loves to be on the road” and “he always makes time for a personal contact,” but most of all, Moresco says, “He’s got kind of an infectious personality. He’s full of joy.”

Henson has now been a Carmelite for 20 years. When not working, he hikes and works out, reads fantasy and adventure novels as well as books on Pope Francis. While he may have been uncertain about his call in the beginning, he has thrived on the order’s charism of prayer, community, and ministry.

“Prayer has to be a daily part of our lives,” Henson says. “What Carmelite tradition has taught the world is that prayer can be anywhere and everywhere in the day. Carmelites are known for praying outside of the box.”

Henson brings to his ministry a “great respect for the discernment process,” Moresco says. “It’s not about getting people in the door, it’s about walking with them, helping them discern their vocation. He’s very good at bringing his own experience to that. Yes, he joined a little bit later,” having earned a college degree and considered marriage and children instead. In working with inquirers, Henson focuses on “how to do this discernment really well, honoring the journey of each person.”

When it comes to vocation, Henson believes the contemplative, prayerful approach of the Carmelites is a good one. “When God calls,” he explains, “there’s no hurry.”

Related article: vocationnetwork.org, “Know thyself: A priest finds his way,” Vision 2014.

Tags

Related

- Taking a chance on God: Profile of Father David Gutierrez, C.M.F.

- About-face to the priesthood

- Moved by the power of the Eucharist: Profile of Father Duy Henry Bui Nguyen, S.C.J.

- No regrets: A grateful priest takes stock

- We’re different—in a good way: Profile of Father Roberto Mejia, O.Carm.

- Man with a mission

- Monastic life is habit-forming

- Ministering to migrants in a carport cathedral

- Connections make the man: Profile of Father Kevin Zubel, C.Ss.R.

- A priest (who’s been there) responds to the pain of addiction Read More

Most Viewed

- Find your spirituality type quiz

- Questions and answers about religious vocations

- Celibacy quiz: Could I be a nun? Could I be a brother? Could I be a priest?

- Resources for older discerners or those with physical and developmental differences

- About Vocation Network and VISION Guide