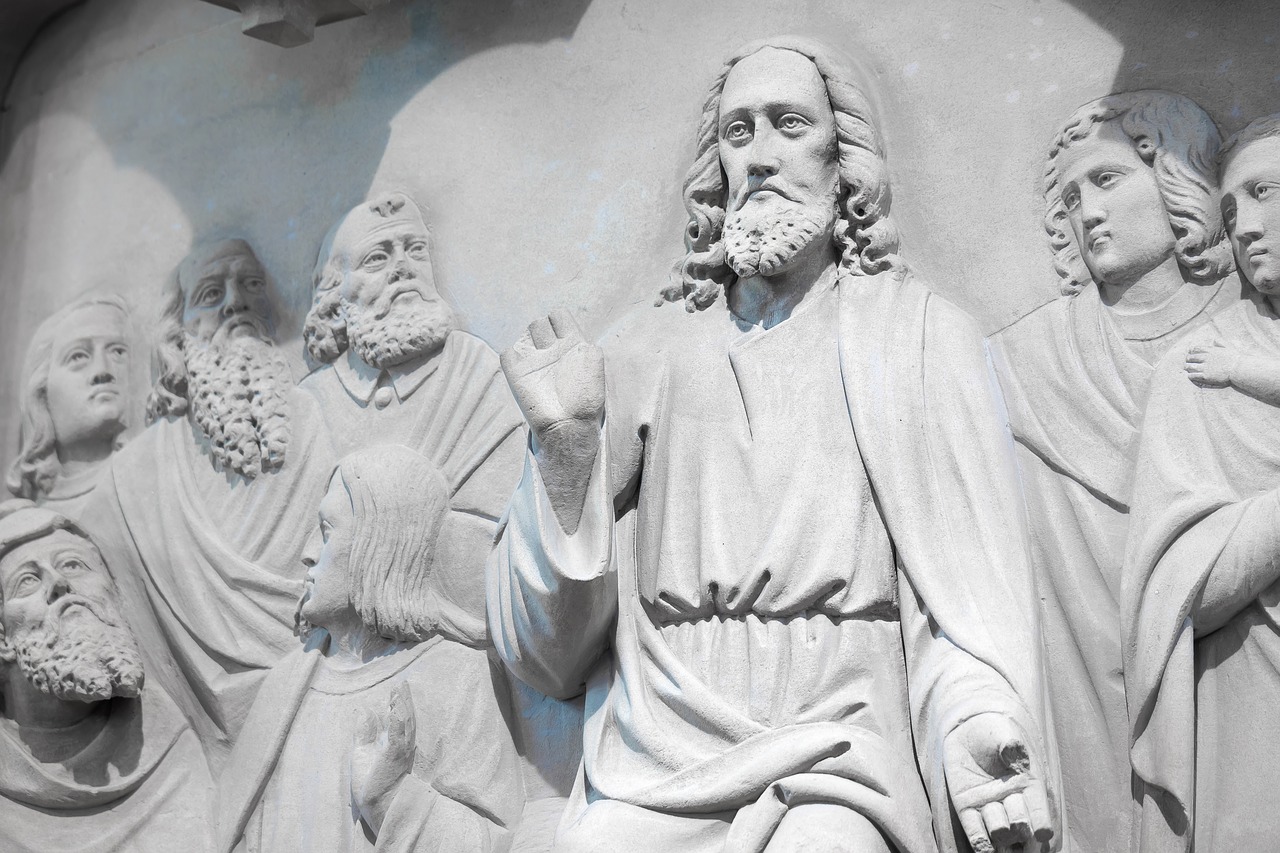

For Roman Catholics the unity of the church is one of its greatest possessions and that includes its teaching authority, or magisterium. We don’t go it alone as Rambo-style disciples. We are church, all of us together. The great unity prayer of Jesus at the Last Supper reveals his concern that the church remains “one” in spirit and truth.

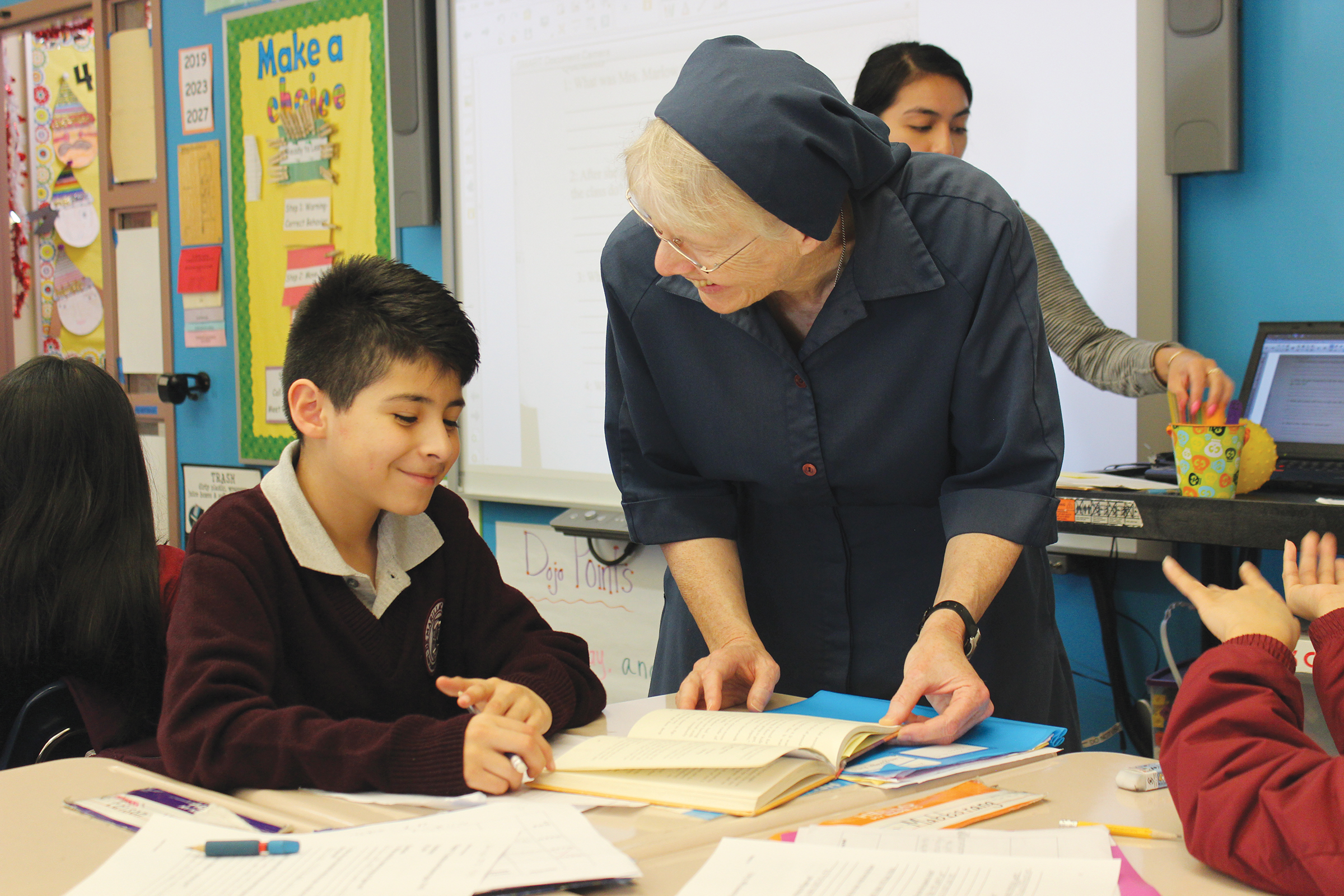

The institution of the church has many names and plays many roles in the lives of believers. The church is a mother, giving birth to faith through its preaching mission. The church is a servant, continuing the ministry of healing and the restoration of hope that Jesus practiced. And the church is a teacher, bringing the light of truth to every generation in matters of faith and morals.

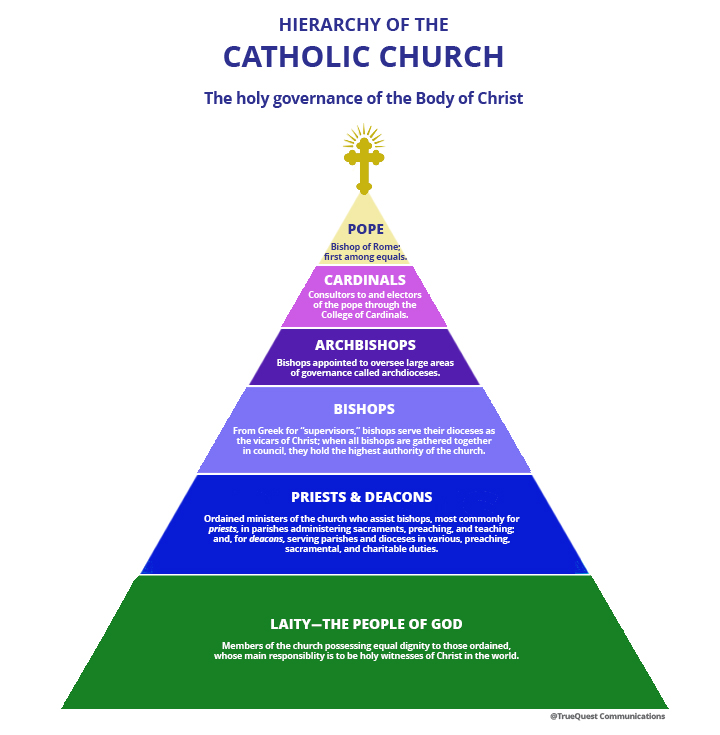

Because the church’s precious unity depends on our profession of a common creed and a common understanding of the faith, Catholics rely on teachers to protect the coherence and integrity of the gospel message. Each bishop exercises the teaching authority in his diocese. He doesn’t act independently but in concert with the bishops of his nation or region, as our bishops do with the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB).

In turn, each bishops' conference exercises its teaching role in keeping with the magisterium (teaching office) of the episcopal college—all bishops together throughout the world who meet in periodic synods to discuss contemporary concerns. The pope is the head of the episcopal college and can exercise the supreme teaching authority of the whole college.

In these ways the magisterium ensures that careful theological reflection, and not only reaction, remains at the root of the church’s message.

—By Alice Camille

Scripture

John 17:20-26; Mark 16:15; Matthew 28:18-20; 2 Timothy 2:2

Books

Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium by Francis A. Sullivan (Paulist Press, 1996)

Turning Points: Unlocking the Treasures of the Church by James Philipps (Twenty-Third Publications, 2006)

Magisterium: Teacher and Guardian of the Faith by Cardinal Avery Dulles (Sapientia Press, 2007)

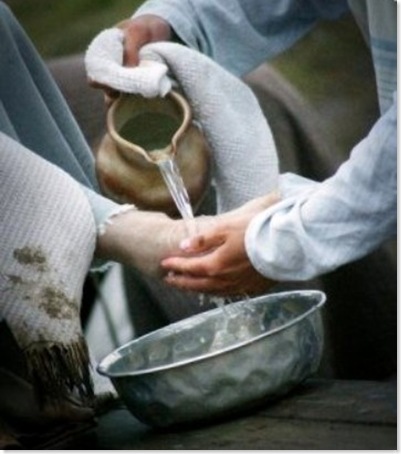

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.